It all begins with a story …

Illustrators and readers are pretty much seeking the same thing when they go looking for a terrific story ...

Terrific stories happen when an author knows how to pull the reader into what’s happening … pull them in until the reader is empathetic to the characters and the “movie” begins playing in the reader’s head. Then the reader isn’t merely a sidelined observer, but is experiencing and feeling everything the characters are experiencing and feeling.

That’s tough enough to pull off in a 500-page novel. Logic suggests that it would be a lot easier in a 32-page children’s book, but that’s not necessarily so. Fewer pages and a simpler plot require the writing to be absolutely tight and spot-on. There’s no space for rambling and chasing rabbits in a children’s book, but there’s plenty of room to pack in all the energy and life you can stuff into it.

First you need to know the basic formula for writing and crafting a story, which you can find in my article, Arranging Words. Or take a class, or read a book, or watch a YouTube video … there’s no end of opportunities and experts who can teach you how to write. Or draw …

Writers and artists have similar journeys when learning and executing their craft … they can learn all the rules and formulas and techniques, and they can execute those perfectly, and still end up with flat, lifeless work.

Memorize the formulas, master the techniques, master your medium, but if you want to grab and engage your readers fully in the experience, you’ve got to get that movie running inside your own head first … the sharper and more detailed you can visualize and imagine it in your own head, the better you will be able to write it all down. But don’t just tell the story, show the story …

Telling the story is when you just state the facts. The facts enter the reader’s head and just kind of sit there, inert, because, unless the reader initiates a response, the text doesn’t really invite a response:

The puppy ate Susie’s homework, and she was mad.

The reader knows that the puppy did something bad and Susie had a logical response to that unhappy situation. The reader may even sympathize with Susie, but it’s still something that happened to just Susie. We don’t have to guess her reaction, the text tells us plainly “she was mad”. An exclamation point would add a little energy to it, but it’s still just a stated fact about a circumstance that happened to someone else.

So let’s show the reader instead …

When you show the story, you draw the reader into the scene:

Susie walked into the room, and, Oh, NO! Her new puppy was chewing and tearing paper … her HOMEWORK!

Now you’ve created a word picture of a scene …

1. A character — accompanied by the reader — walks into a room. The reader is just a static observer until they get a heads-up, Oh, NO!, which alerts the reader that a surprise is coming … now they are engaged and anticipating what’s next ….

2. Instead of a flat statement, The puppy ate her homework, we made a word picture describing the scene, Her new puppy was chewing and tearing paper. The reader can instantly visualize the mess and a cute puppy. They are seeing it along with Susie, and probably holding their breath … somebody’s in big trouble! But it’s just an innocent little puppy … he didn’t know … now the reader is emotionally engaged.

3. Then the surprise punch, it’s her HOMEWORK! Now the reader’s sympathies shift from the innocent little puppy to poor Suzie! All that hard work destroyed! Yikes! Now the reader doesn’t have to be told what Suzie might be feeling, because they just felt it, too!

Word pictures like this work in any genre. Whether it’s an adventure, a horror story, a biography … use word pictures to pull the reader in and engage their emotions. Don’t merely tell them it was heart pounding, scary or inspiring … make their heart pound, make them shiver with fright, and inspire and motivate them to do great things that will change the world.

This is why reading is so much fun, because a reader is fully engaged with their mind and their emotions. Good writing draws them in and suddenly they are having experiences and meeting new people through the books they read.

The Unique Genre — Picture Books

Older children and adults have longer, more complex books because they have learned to visualize and engage with reading material. For younger children, picture books are teaching them how to do just that: how to form mental images to go with the words they hear and read.

In picture books, the story is actually told twice.

First it’s told in words, and then it’s told again — simultaneously! — in images.

Images in picture books are generally created by artists in various mediums, but photography can be used, too.

The images in pictures books make all the difference as to the book’s success. Even when the writing is just so-so, terrific images will save the day. But if the images are poorly planned or have no energy, the best writing in the world won’t make a bit of difference.

Sometimes the words say more than the images show. Sometimes the images add more to the story than the words say. Words and images in a picture book can enhance each other and should always agree with one another. When they say different things it’s confusing to the reader. Words and images should not conflict nor compete with one another.

Some picture books don’t have words at all, only the images carry the story along. These stories are generally submitted to publishers by an author who has a great idea for a story to be told only through a series of images. They plan out what should be shown on each page and in what sequence. Then an artist/illustrator is chosen who will make it happen. Although there's no written text, the author is still given credit for being the original creator of the work.

But the vast majority of picture books do have written text. And once the story is written, it’s time to design and layout the book and add the images.

Off to the Illustrator …

In traditionally published books, the publisher will select and hire an illustrator and the author will not likely be involved in the process at all.

Self-published authors will be hiring their own illustrators. You will need an artist who is an illustrator and a graphic artist to layout the book. Sometimes you’ll find both of those in one person, but sometimes you will need 2 separate people. If it’s 2 separate people, get the layout done first, so the illustrator will know the physical space/limits where the illustrations will be. To get you started with the process of finding an illustrator, click here.

Before sending a manuscript to an illustrator, make sure it’s in its final form, i.e., it’s been fully edited and ready to insert into a layout. Little tweaks and corrected typos will come up and that’s fine, but you don’t want sweeping changes that might rearrange whole paragraphs or delete or add substantial amounts of text that will affect the layout of the pages, and size and placement of the illustrations.

Illustrators get all kinds of manuscripts coming into their inbox, both well written and not-so-well written.

If you’d like to see the entire process, from inspiration to writing to layout and art to final book, check out my 6-part series, Planning Your Book.

For now, let’s use our 2 examples from earlier in this article to see how an illustrator might approach either a poorly written or a well written manuscript.

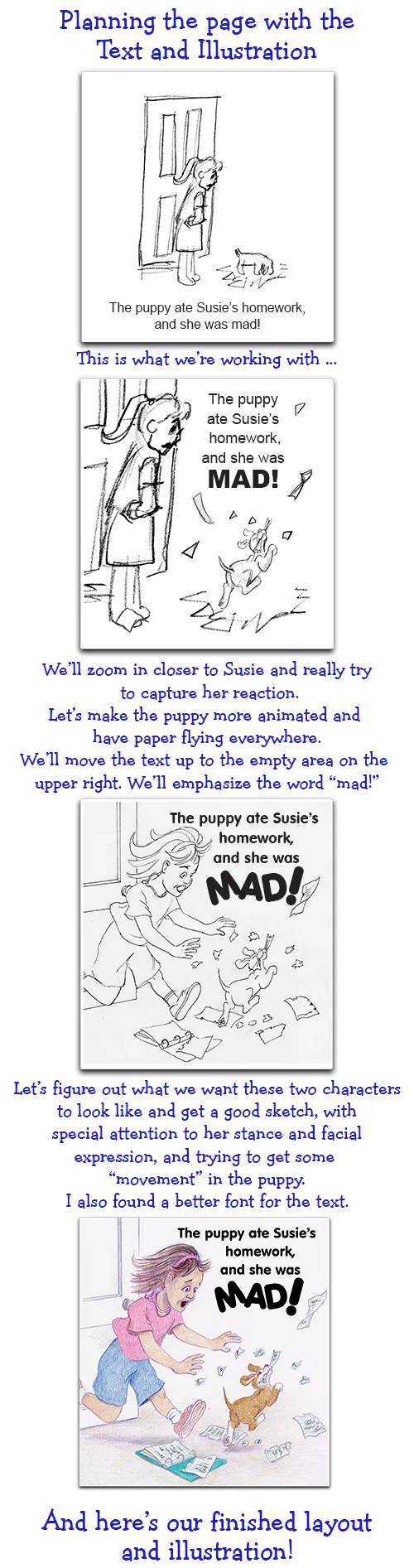

Salvaging the Poorly Written

Good writing is all about capturing a reader’s interest and making that “movie” play in their head.

Bad writing just kind of lays there and doesn’t do much of anything.

Fortunately, a good illustrator has been gifted with an ability to “see” what’s not even there, and they’ll make up their own movie! That’s what will happen when they get writing like this:

The puppy ate Susie’s homework, and she was mad.

The first thing they’ll do is change that period to an exclamation point:

The puppy ate Susie’s homework, and she was mad!

The exclamation point helped a bit, but that little statement is still rather dull. So our illustrator will pick up a pencil and begin pondering and making rough thumbnail sketches ...

Hmmm ... let's focus on Susie being mad and use the bottom right thumbnail, which will give us some space to play around with the typed copy ...

Even with a manuscript that's a little lackluster, a picture book can still have some pizzazz!

So what about manuscripts that are better written ...

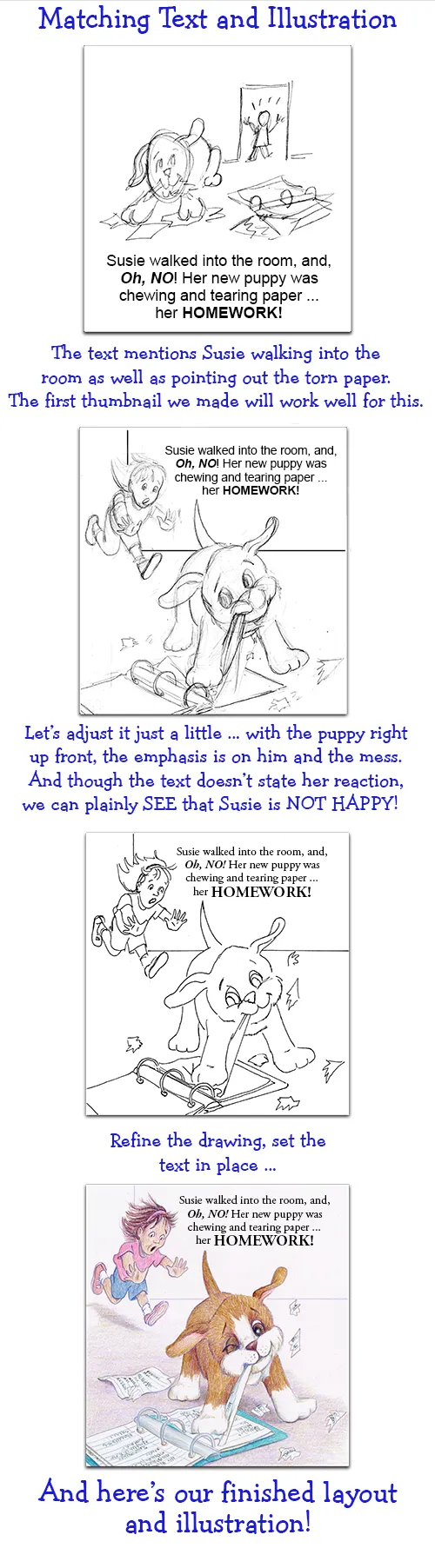

Making the Well Written Even Better

There’s nothing more fun for a picture book illustrator than getting a terrific manuscript. Well written manuscripts will have a reader seeing the action in their head before they ever see pictures on a page.

Susie walked into the room, and, Oh, NO! Her new puppy was chewing and tearing paper … her HOMEWORK!

Here, the emphasis is on the puppy and the torn paper, so that should be highlighted in the illustration. The first thumbnail we did will work well for this ...

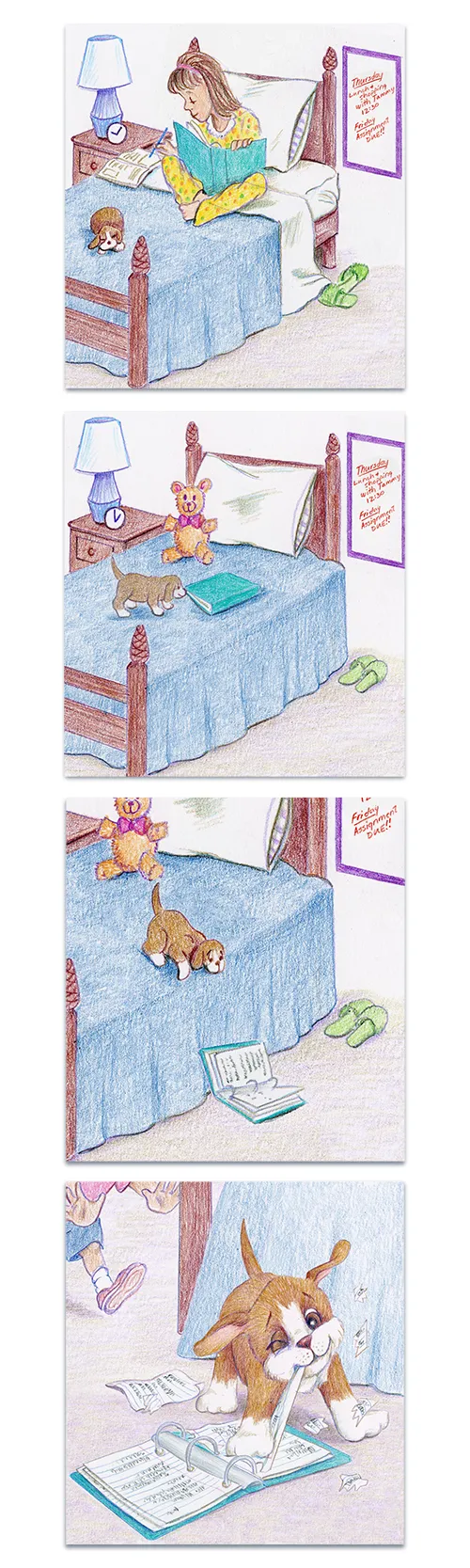

All Images — No Text

I said earlier that some picture books don’t have words at all, only the images carry the story along. These are usually for the very youngest readers, like alphabet and numbering books. Or sometimes they are beautiful art books, filled with full color paintings of nature or animals.

These books are mostly for looking at with a parent, and may or may not have any story to tell. If there is a story, then it will be told with sequential images that progressively tell the story, and capture all the emotions and energy at the same time.

That's quite a challenge for an illustrator, but what an interesting challenge!

The pictures need to be detailed enough to get in all the details of the story ... but you don't want so much detail that the story gets bogged down, or moves so slowly that the reader loses interest. You want your teader to keep turning those pages!

But heads up ... even for books with plenty of text, this is a good test for an illustrator to measure their own work by. Take away the all the typed copy and look at just the illustrations ...

• Do they almost tell the story, even without the words?

• Do you get a feel for the story in the right sequence as it unfolds?

• Does the action "flow" logically and seamlessly from page to page?

• Do the images look like they all go together, like parts of one unit?

• Have you captured the tone/mood of the story?

• Have you captured the personalities of the various characters?

• Is coloring and drawing consistent throughout?

• Are the characters recognizable as the same characters every time they appear?

Scrutinizing your work like this is invaluable. Even better, have someone else do it who is seeing it fresh for the first time. Things will stand out immediately that have been invisible while you've been working day after day.

Do it several times throughout the process, beginning with the roughed out layouts, then during the process and when checking the final work.

The best illustrations do the same thing well written words do ... they draw the viewer in to experience a great story told well ...